London Silver Vaults

London has a rich and vibrant history, and the origins of The London Silver Vaults and its surrounding areas can be traced back to the 13th Century

The London Silver Vaults, situated beneath the north end of London’s Chancery Lane are located in an ancient area, marking the very western boundary of the City of London, established in 1160 by the Knights Templar who owned the land.

Opened officially in 1953, the building’s heritage can be traced back to 1227, when the street became home to the Lord Chancellor’s palace (from which Chancery is derived). Henceforth it was associated with the legal profession, and various Inns of Court, including Lincoln’s and Staple Inns, flourished around it.

The famous Agas Map of 1561 shows just how rural the area was during the Elizabeth period. Chancery Lane is marked in yellow, and the London Silver Vaults lie beneath the fields to the east of the street. It is notable on all respected London maps throughout eight centuries how little the layout of Chancery Lane and Holborn, and their smaller tributary streets, have changed.

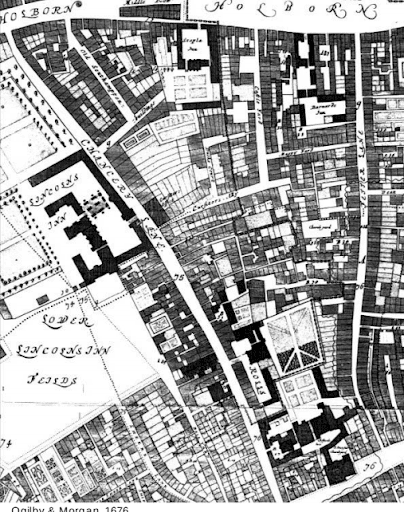

Only 150 years later, in 1676, a subsequent map by Ogilby & Morgan shows the rapid evolution of Chancery Lane into a sophisticated legal mini metropolis, still on exactly the same street lines.

The Georgian period saw little change in Chancery Lane and the surroundings.

The area had been untroubled by the Fire of London in 1666, and was a prosperous professional marketplace dating back many centuries.

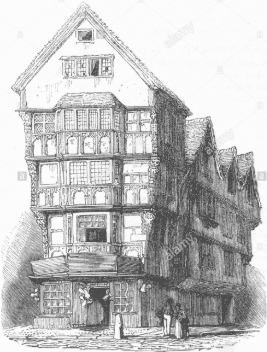

It was not a shopping street that needed to keep up with the latest fashions, and was very much all about business, with many of the buildings dating from Tudor times.

Old building, Chancery Lane c1550, from engraving dated 1845, pictured right.

The prosperity of the nineteenth century brought many changes to London, but one of the most dramatic in terms of infrastructure (if perhaps the least dramatic to the casual observer) was the introduction of London’s underground railway network.

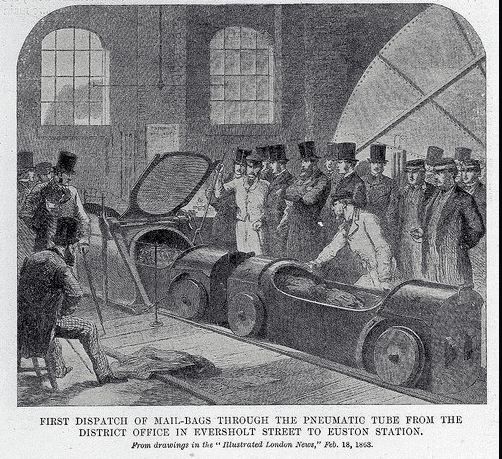

In January 1863, London opened ‘The Underground’ between Paddington and Farringdon using gas-lit carriages pulled by steam trains. Lesser known is the concurrent development of the London Pneumatic Despatch Company, which also opened for business in 1863.

It had been proposed in 1859 by In 1859 Thomas Webster Rammell and Josiah Latimer Clark for ‘the more speedy and convenient circulation of despatches and parcels’.

Pneumatic or ‘atmospheric’ railways, as they were known, were remarkable pieces of Victorian engineering, using differential air pressure to provide propulsion for a railway car. Essentially, the air pressure was lowered in a sealed tunnel in front of the railway car to create a vacuum, sucking the car along a continuous pipe like a piston.

In London’s increasingly busy postal service, now groaning beneath the weight of paper generated by an empire on which the sun never set, the subterranean pneumatic railway seemed like the perfect answer.

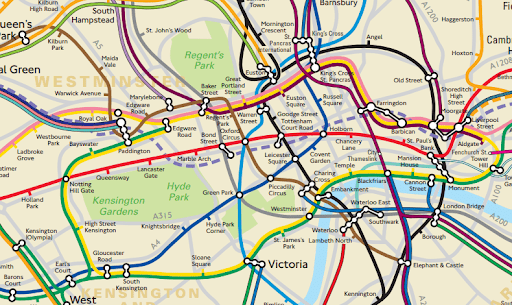

The original line ran from Eversholt Street to Euston Station, but subsequently, in 1865, a line from Holborn to Gresham Street, via the huge General Post Office on St Martin’s Le Grand was under construction. It is a largely unknown fact that London’s Underground system does not correspond to Harry Beck’s 1931 map, but in fact in Zone 1, follows the ancient road system, thus:

The main reason the Underground or ‘Tube’ tunnels follow the roadways is that the government had to compensate property owners if they tunnelled beneath their holdings, but to dig beneath roads cost them nothing.

In 1866, there was a financial crisis in the City of London caused by the collapse of the Overend, Gurney and Company, the ‘banker’s bank’, with debts at the time of more than 11 million, and work on the pneumatic railways was forced to pause. However, a ⅜ mile pneumatic tube had been constructed at vast expense. It began again two years later, and was finally completed in 1869, stretching to St Martin’s le Grand, and cars full of mail could then travel from the General Post Office to Newgate Street in under 17 minutes, reaching speeds of up to 60mph.

Unfortunately, atmospheric railways are notoriously unreliable, and cars full of parcels were continually stuck in the tunnels, so by 1874, the Post Office abandoned the use of the tunnel running west-east beneath the north end of Chancery Lane. It did not, however, stay abandoned for long.

Key to the construction of the pneumatic railway, already known in 1864 as ‘the tube’, was that telegraphic wires were laid down at the same time, beginning December 1864. In addition to this, in 1838, the new Public Record Office had been created, ostensibly fronting onto Chancery Lane, but in fact a vast complex that took up acres of land on the east side of the street, stretching all the way to Fetter Lane. It replaced the old Fetter Lane record office, which had incorporated the church or chapel of the Rolls, and the frontage visible now (as Kings College University campus) was built in 1851-1858 by James Pennethorne. Like the telegraphic wires, the Record Office would play an integral part in the genesis of the Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company in years to come.

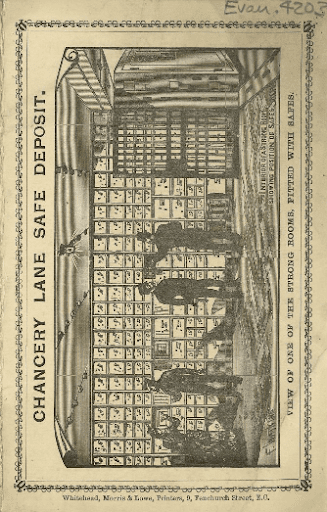

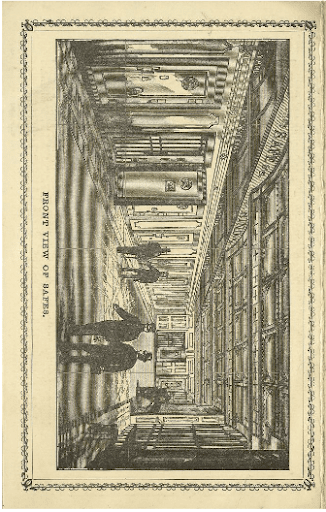

Upon the closure of the pneumatic railway, a group of enterprising City of London businessmen approached the London Pneumatic Despatch Company to purchase the stretch of tunnel between Holborn and Hatton Garden with the intention of creating safe storage in the form of safety deposit boxes and strong rooms. This was a considerable undertaking, and it took until the 7 May 1885 for the Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company to open for business at 61 & 62 Chancery Lane. leasing safe deposit boxes and strong rooms for the ‘Safekeeping of Plate, Jewels, Bonds &c.’ The address was 61 & 62 Chancery Lane, situated on the east side of the historic London street, near the busy thoroughfare of High Holborn, advertised ‘telephone rooms’ for the use of renters as one of the main attractions.

Pamphlet courtesy British Library

The Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company

The Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Co., was only the second non-bank-based safe deposit premises in the United Kingdom; the first was The National Safe Deposit Co., of 1872, founded in Queen Victoria Street, City of London.

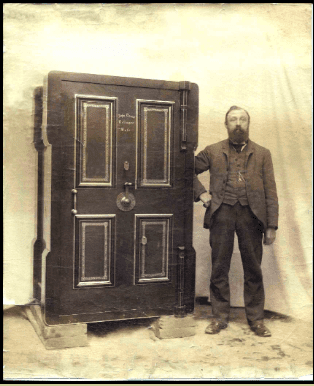

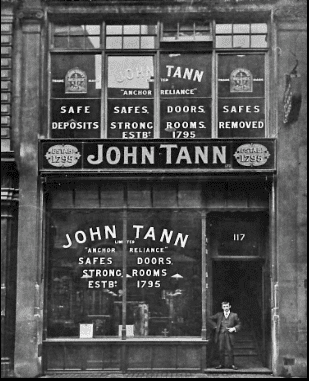

(The only other significant openings of private safe deposits in British history are Harrods, 1896; St James’s Safe Deposit Co., Manchester, 1912, London Safe Deposit Co., Lower Regent Street, 1931; and Selfridges, Oxford Street, 1930. The Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company was notable for its use of the highly regarded John Tann Safe, also used by the Bank of England, and the most famous of all Victorian safe-building families.

Images Courtesy John Tann Family

So confident of the security of their safe deposit, that The Company, in 1893, advertised ‘in urgent terms for a burglar or two’ under the headline ‘BURGLARS WANTED’. The Company allegedly was, ‘in fact, very anxious that some enterprising Bill Sykes should try his hand on the invincible premises at Chancery Lane’. The 1890s were of paramount importance to the reputation of the safe deposit company.

The presence of private telephone rooms for renters meant that the Safe Deposit was soon in high demand from dealers in diamonds and antique silver from the nearby diamond District Hatton Garden: it was a convenient and secure place from which to do business, a short walk away from their retail premises.

By the turn of the twentieth century, the Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company was storing everything from personal possessions to gold ingots, and in one case, the symbolic safekeeping of a single penny. The eccentric gentleman in question died in 1924, having kept the coin in the otherwise empty strongroom for 30 years. Upon his death, he estate was worth in the region of half a million pounds. His heirs took the penny away.

Image courtesy Hirschfields of Hatton Garden, established 1875

After a prosperous few decades, disaster struck the Company on the first night of the Blitz at 2259 on September 7 1940, when the road in front of the Safe Deposit was struck by 2 incendiary bombs. However, the strongrooms and safe deposit boxes were either destroyed or fatally compromised on the 25 of the same month be a direct hit (the same night Staple Inn was bombed): the image below depicts all that was left above ground the following morning.

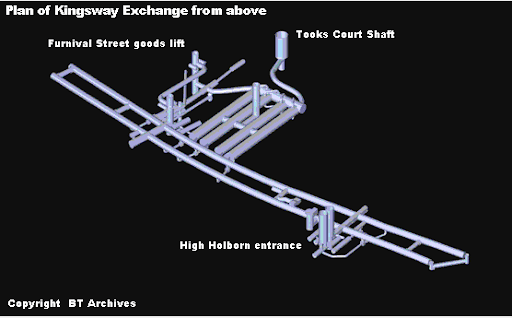

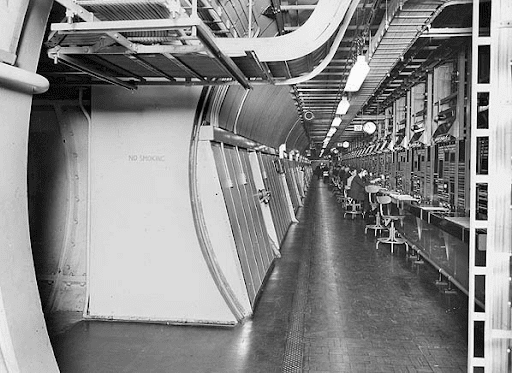

The Blitz mobilised the British government to immediately create eight deep level air raid shelters in London, with the aim of holding 10,000 people in each shelter. Chancery Lane Deep Shelter is the only one on the Central Line: the others are Belsize Park, Camden Town, Goodge Street, Stockwell, Clapham North, Clapham Common and Clapham South, all on the Northern Line. Chancery Lane deep shelter was, however, unique in the that it was not truly intended to offer shelter to large numbers of ordinary London citizens: the extensive network of telephone cables installed in the tunnels meant that it was soon set up as a communications hub for government personnel during the war, with some of the most sophisticated technology of the time. The government took over the old Safe Deposit premises and converted them into part of what became Chancery Lane Deep Shelter and Kingsway Exchange.

Courtesy BT Archives

In 1950, the threat of war was over, although the Kingsway Exchange was kept open until 1980 as a Cold War communications centre. The Chancery Lane deep shelter was redundant, and many of London’s dealers again needed safe storage for their goods. After a period of negotiation, rebuilding above ground, and extensive subterranean works, The Chancery Lane Safe Deposit Company and London Silver Vaults opened in 1953 at 53-64 Chancery Lane, housed in part of the deep shelter running parallel with the street itself.

After six decades, they remain the largest retail space for antique and modern silverware in the world, and many of the businesses are multi-generation family enterprises.

© Lucy Inglis and Simon Surtees

REFERENCES

Atmospheric Railways: A Victorian Venture in Silent Speed (Newton Abbot: David & Charles, 1967) p.117

Railway News, 17 December 1864 p.36

An Almanac for the Year of Our Lord, 1888, p.251

Printers’ Ink (Philadelphia: Decker Communications, Incorporated, 1893) Vol.9, p.319

The Jeweler’s Circular (New York: The Jeweler’s Circular Publishing Company, 1924) Vol.89, Vol.57 p.116